PART 1: Humble beginnings

During the summer I decided I wanted to pursue a minor in mathematics alongside my studies in Computer Science. I had liked the math courses during my first year of studies, so it seemed like a natural step for me.

When I looked through the courses in the mathematics minor, I realized that there weren't that many options to choose between during the autumn. The course in Partial Differential Equations stood out to me. I knew it would be difficult, but I didn't think much of it and signed up to the course.

Fast forward to September and the course started. After attending the first lecture I quite quickly realized I was in a totally different world than what I had imagined.

I learned two things:

-

Because of my studies in CS, I had missed out on both the Linear Algebra and Vector Calculus course in the spring earlier that year. This turned out to be a huge pain point. The course built heavily on the results from these courses. There was also a lot of mathematical notation that I had never seen before.

-

This wasn’t your average first-year engineering math course. This was a math course. The proofs and results being made were ten times more rigorous compared to the last math course I had taken. When stating a theorem or result, it led to dozens of more corollaries.

I remember it took about two weeks before I was completely lost and had fallen off-track.

PART 2: Why are PDEs so difficult?

Let's take a step back and start with a simple question. Why are PDEs so notoriously difficult?

In the course, we focused on three PDEs that have crucial applications in especially physics:

$$ \text{Wave Equation:} \quad u_{tt} - \Delta u = 0 $$

$$ \text{Heat Equation:} \quad u_t - \Delta u = 0 $$

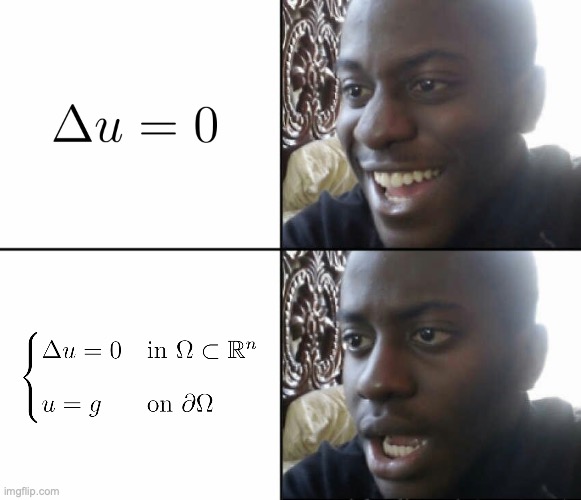

$$ \text{Laplace Equation:} \quad \Delta u = 0 $$

These three equations are all very useful when modelling real-world phenomena. They all depend on the famous Laplacian operator, which is the sum of the second order partial derivatives:

$$ \Delta u = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x_i^2} = \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x_1^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x_2^2} + \cdots + \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x_n^2} $$

Not too hard? The difficulty isn't to write down the equations themselves. It's solving them that is the hard part, and especially where you solve them. There are many different factors that impact the solution of a PDE:

- Dimension: which dimension are we talking about? 1D, 2D or 3D? or $n$D?

- Domain: whole space $\mathbb{R}^n$, half-space $\mathbb{R}^n_+$ or a bounded region $\Omega$?

- Boundary and initial conditions: Dirichlet, Neumann, Cauchy or a mixture?

- Homogeneity: with or without source term $f$?

Let's take dimension as an example. In 1D, the heat equation behaves very differently than the heat equation in 3D. In higher dimensions, heat has more directions to spread into, so the concentration at any given point decreases more rapidly. Similarly, when solving the wave equation, it behaves fundamentally differently in 2D and in 3D.

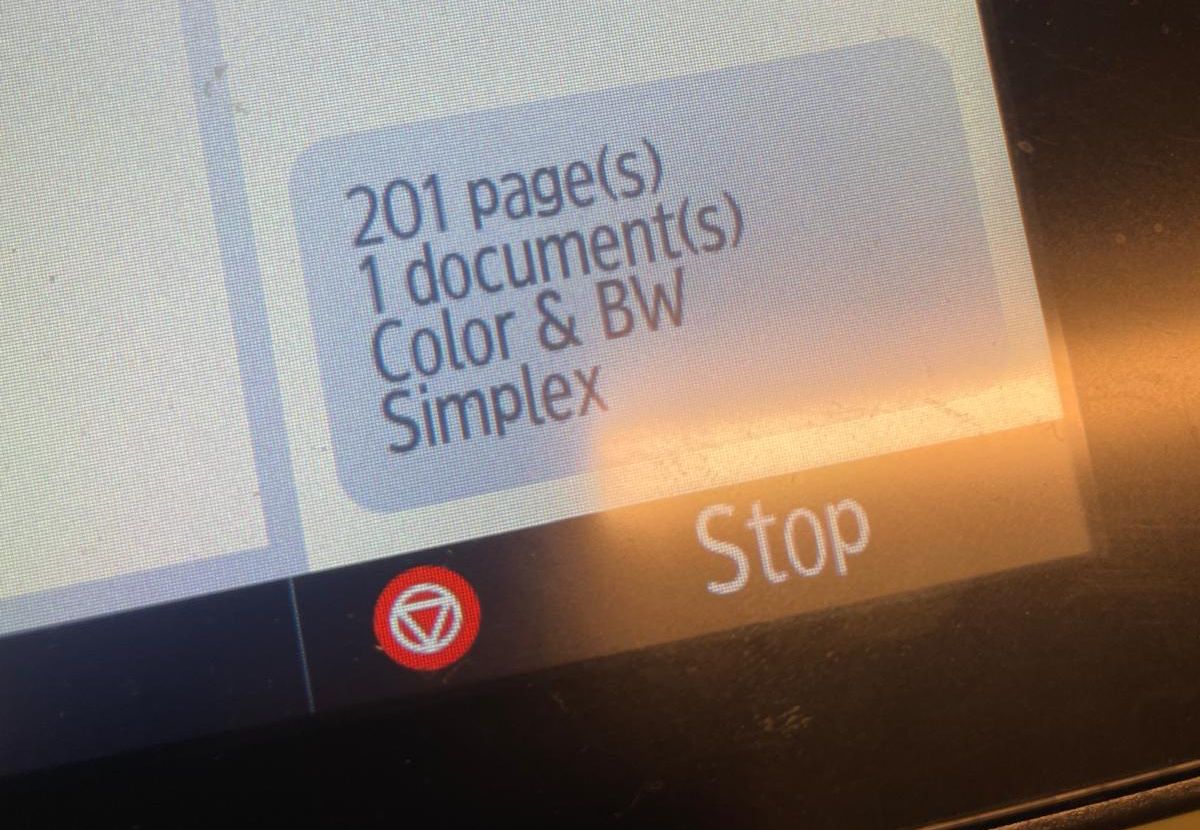

And this is just the start. What if we consider this on a sphere in N-dimensions? What if add a minus sign here? What if we instead consider a parabolic boundary? All of these questions lead to widely different results, in many cases entirely new formulas which haven’t been considered before.

PART 3: In the trenches

In retrospect, September and October were some of the best months of my life. I had recently started working at Intergrid. Additionally I was a team lead at Slush.

However, at the same time, the course proceeded at what felt like record speed. After falling off-track in September, it was quite hard getting back on track. The reason for this was that nearly everything built upon earlier results in the course. It therefore felt very hard to get back on track if you even for one week stopped following along. This may feel obvious in retrospect, but it hit really hard in this course.

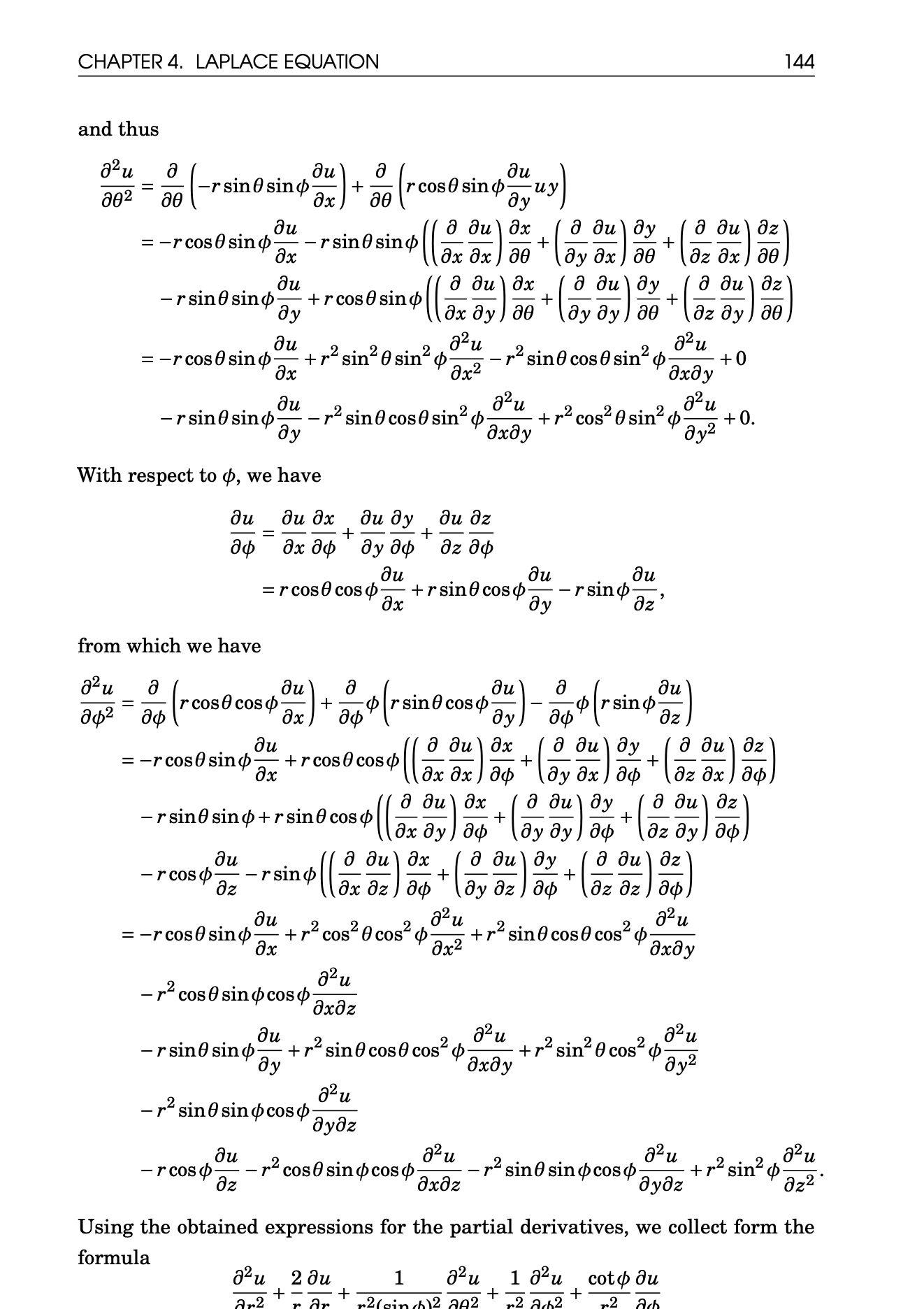

Trying to read the textbook on a computer screen started bothering me. One day I was sitting in the library when it struck me that I could just print out parts of the textbook on physical paper using the printers on campus.

I tried to edit the PDF of the textbook to only contain the pages that I wanted printed out, but I was unable to. Therefore I just sent the entire PDF to the printer and figured it would probably ask before printing 200 pages.

It turns out it didn’t. I therefore accidentally printed out the whole textbook. The printer was surprisingly fast at its job, but I still stood there embarrassed for five minutes.

PART 4: The comeback

During the week before Slush in November, I looked through past exams and I realized I couldn’t even map some of the problems to their corresponding chapter in the textbook. I needed to get back-on-track as quickly as possible. However, without sacrificing sleep, the calendar looked pretty full up until the exam week. I had other exams as well.

It ended with me waking up on a Saturday with less than 48 hours to go to the exam and around 200 pages of math texts to read. It felt quite lost, but I decided to try my best. For two straight days the only thing I had on my mind was PDEs. I think I studied for a combined total of 30 hours during these two days.

And it somehow worked. When the exam started, I realized I was able to solve most of the questions. It felt quite incredible, because just two days before, I would have been able to solve at most one.

I agree with Robin in his post; this course made you feel like a mad scientist. If this course taught me one thing, it is to push your boundaries even when it feels impossible. Because it might just work out. And worst case scenario? You'll have a great story to tell.

PART 5: My favourite result

I would like to end this post with one my favourite results from the course. It wasn't directly stated in the course, but I found it after a bit of digging. The result can basically be stated using only words.

When solving the wave equation there is a stunning dependence on the dimension that completely changes the physical behaviour of waves. To understand this, we need to first talk about Huygens' principle.

Huygens' principle says that sharp disturbances should propagate as sharp wavefronts, leaving complete silence in their wake. Imagine clapping your hands in an empty room: you hear a sharp sound when the wavefront reaches you, and then perfect silence. No lingering echoes or trailing vibrations are left behind. Or consider turning on and off the light, it will either be dark or bright.

This is exactly what happens with the 3D wave equation. The mathematics confirms the physics: if you solve for a point impulse, you find that the solution is concentrated entirely on an expanding spherical shell. Inside the sphere, where the wave has already passed, there is silence ($u=0$).

But solve the exact same equation in 2D, and something bizarre happens. The sharp wavefront still arrives, but it's followed by a persistent trailing disturbance that never completely vanishes. Drop a stone in a pond and you'll see this: the ripples continue long after the stone has been dropped. Therefore the 2D wave equation doesn't satisfy Huygens' principle. This is what can be considered a "dimension leap".

The stunning general result is that Huygens' principle holds in odd dimensions (1D, 3D ...) but fails in even dimensions (2D, 4D ...). The same wave equation, the same mathematical structure, but whether you live in an odd or even-dimensional universe determines whether the waves leave trailing echoes.

Casimir Rönnlöf, December 2025